Women don’t have to be perfect in math or science to consider becoming an engineer. Engineering skills can be applied to a range of fields and corporate opportunities.

Christine Georgia, Assistant Dean & Director, Women in Engineering Program, Principal Academic Professional, G W Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

Christine Valle

In France, engineering is a well-known and respected field. Many young people choose it as a career if they have math and science skills and interest. While Christine Georgia did have those skills, engineering was not her first choice. She initially wanted to pursue a career as a writer or artist. However, both her parents were engineers — and thus they were adamant that she obtain an engineering education.

“I very much wanted to write,” she said. “It was hard to forego that goal, but in retrospect now, I am grateful, particularly for my dad who really stood his ground and kind of said, ‘absolutely not.’ And engineering has become, or has turned out to be, much more fulfilling than I thought it would be when I was 16.”

Now a naturalized U.S. citizen, Georgia first came to this country when she was 15 years old; her father had received an opportunity to come to the U.S. to work for a subsidiary of a French company that was based in New Jersey.

“He uprooted the whole family, which, being a teenager at the time was very traumatic and profoundly changed my life,” she said. “I ended up finishing my high school years at a French school in New York City in Manhattan. And you’re 16 and you think you know everything and I just thought, ‘oh, the whole country is like Manhattan. This is amazing. I have to come back.’”

She wanted to go to college in the U.S. but her dad, who was quite cost-conscious, forbid it. So, she went back to France for her first degree in aerospace engineering. The Paris college had a partnership with Georgia Tech, so Georgia received her master’s PhD at Georgia Tech in mechanical engineering.

“I started in aerospace, but then met a professor who sold me on a project for my PhD that was going to be housed in mechanical engineering, so I had to switch majors,” she continued. “I got my PhD from Georgia Tech and basically never left the country, becoming a naturalized citizen in 2008.”

Have degree, will work

While Georgia had the necessary degree qualifications for just about any corporate employment, actually getting hired in an engineering field here proved challenging.

“This was 1999. I think part of the situation was with my visa. I was here on a student visa F1, which makes it hard, still to this day, for companies to hire foreign nationals. Also, I was in a research area that was very defense related. I was looking at cracks in military aircraft. The types of companies that were interested in me definitely did not like the fact that I was a foreign citizen. Every country protects its military, so it makes sense. Still, I had a hard time trying to stay in the States. But being an academic is, still to this day, one of the easiest ways to get the green card, which is the permanent work authorization and then from there, five years later, you can apply for citizenship.

“Therefore, I applied to universities and found out quickly that I love teaching, which I never thought would happen. And so I stayed.”

She taught at two other universities before returning to Georgia Tech. One was the University of Maine and the other was Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Arizona.

Working with young women engineers

Georgia Tech has been the number one producer of women engineers in the country for more than a decade. Christine has been running the institute’s Women in Engineering program since 2011.

“I think the program’s success is multifactorial,” she said. “The women who come are attracted by different aspects of Georgia Tech. If I had to narrow the biggest factors, number one is the fact that we are academically rigorous as an institution. Women tend to be risk averse. If they’re going to study something, they want to make sure that this is a good degree from a good school that’s going to lead to a good job.”

“And we are good at specific majors that women seem especially interested in. In Biomedical Engineering, for example, the program that we have here has consistently been in the top three in the nation since inception. Industrial Engineering is another popular major for women, number one for over two decades. Environmental Engineering is in the top three, and then Chemical Engineering is in the top five.”

“In general, women seem to be more socialized to help others, so fields like bio-med and environmental engineering strongly connect with women. Industrial engineering is more systems and business oriented and women also tend to like that. And then finally, chemical engineering, I think chemical engineering is attractive because there’s a lot of ties to chemistry and a lot of women are very strong or really enjoy chemistry in high school. And then, there’s an environmental aspect to chemistry too.”

Challenges in the corporate world

In some cases, gaining the engineering education is the easy part for women. Feeling as though you matter and contribute to various corporate goals can be a challenge. For various reasons, a number of women leave the corporate world after a couple of years. Georgia sees several reasons for this situation.

“I think a lot of this has to do with the individual’s position and the group that she might be in at the company. If you start out as a young woman and don’t see a whole lot of other women around you, that can be very isolating and alienating,” she said. “Another aspect is if women don’t see sufficient opportunities they will leave. Women must also deal with being the dominant care giver to children and spouses, which can force women to take a backseat.”

“Some women, however, will say, ‘I don’t care. I’m just going to power through,’ and they will stick with it. Or they just really, really deeply love the industry or they find some other reason to stay. I’m thinking in particular of one alumna who works in an extremely male dominated field — a railroad company. But she said what she loves about it is that it’s a union job. Her benefits are exceptional and her husband has a medical condition that makes it difficult. So, she sticks it out and she has found ways to make the job interesting and worthwhile for her and her family. Engineering is still very male dominated, and not changing anywhere near as fast as I’d like.”

Being heard

The corporate world can be a challenge for a large number of women engineers. Georgia notes that such experiences are prevalent in industry and it can also be a common experience at the student level in college.

“What I have found, and research concurs,” she said, “is that anytime you are in a group where you stand out in some way, it could be your gender, it could be your race, it could be the fact that you’re a foreigner and everybody else is native born, it could be your sexual orientation, whatever it may be; if there’s less than 30% like you within the group, you will feel self-conscious. Depending on your personality, you may feel intimidated and taken less seriously than the majority group. And so, 30% is defined at this critical mass where the people with the different characteristic will feel less able to speak up and to be treated the same way as the majority group.”

“If you look at majors like biomedical engineering or chemical engineering, pretty much over 50% or very close to 50% of the students are female. Very few of the students in those classes report not being taken seriously. Whereas if you look at mechanical engineering, I will fairly often hear from female students saying, ‘In my design classes where I’m working in a group, the groups are assigned by the professors so I don’t have a say in who my teammates are. If I’m in a group with mostly men — guess what, I’m the secretary, I’m the one who writes the report because women are good at writing, right?’ So, it’s hard to be taken seriously.”

“We at the university are very aware of that. And we have mentoring programs within the major in place. We host seminars where we try to teach women skills on how to tackle this. But again, it’s very situation dependent. Such experiences do not apply to every single woman. Although I will say once they are out in the working world, and especially as they rise up in rank, the likelihood that they’re going to encounter a situation like that goes up the higher up you go, just because most of the working world, engineering or not, is still male dominated. This will be a problem that at some point they’re going to have to tackle.”

“We try to let them know that if they’re suffering from lack of self-confidence and impostor syndrome, all those kinds of things that have been documented for groups that have characteristics that make them minorities within the overall male, white engineering field, first of all, you are not alone. Second, there are strategies, and third, you get better. I think with those three aspects, it will help. It helps if women get out of their own isolation. It can really distort the picture for you in a number of ways and you realize you’re nowhere near as bad as it seems.”

Full STEM ahead

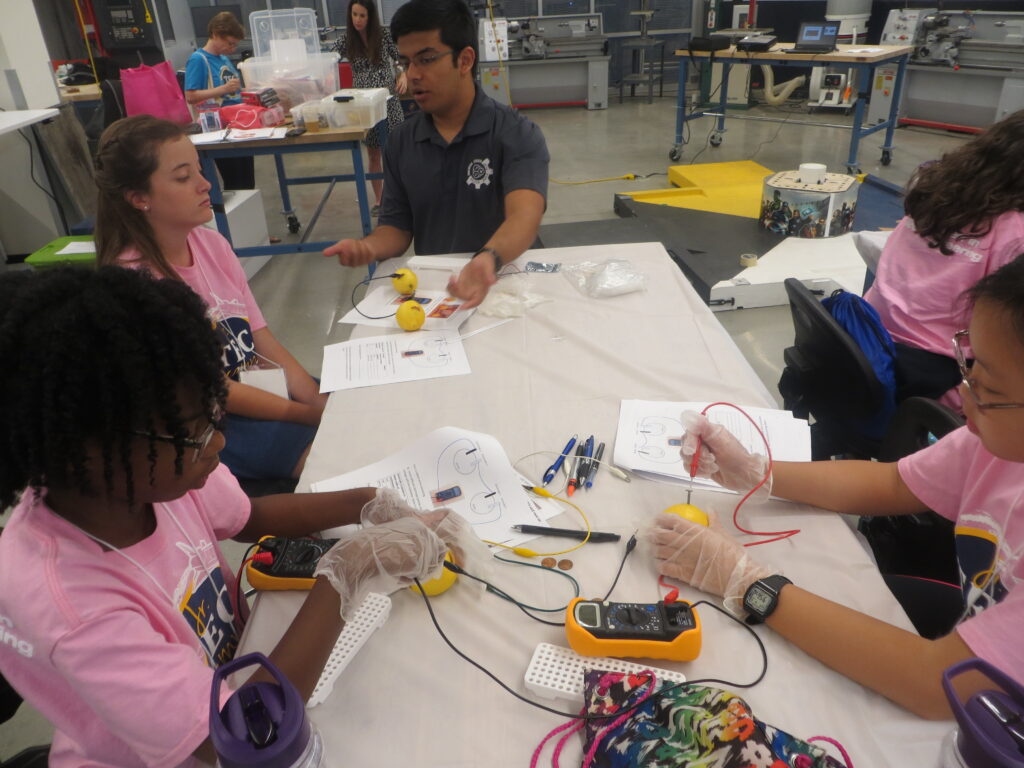

Georgia, in her capacity as director, spends at least half of her time doing K-12 outreach. Georgia Tech has hosted summer camps for elementary school girls and middle school girls. Plus, the institute offers one-day visits for high school female engineering students, giving them an opportunity to talk to faculty and students in the college of engineering about the different majors and how to apply and what exactly is engineering and all of that.

In addition, Georgia Tech has a program to reach out to local schools to reach groups of potential students not strongly represented in engineering fields.

“And we partner with school teachers and principals to go into the classroom and talk to the kids about engineering — and sometimes we do hands-on activities with the kids. We really like that because we’re in the heart of Atlanta,” she continued. “There’s so much demand even within the city of Atlanta and even more in the state of Georgia in terms of exposing young kids, men and women for that matter, to engineering and not every kid will be able to come to campus. It’s good when we can go out to the schools.”

Engineering not well known

Georgia has an international perspective on the field of engineering. She finds that in the U.S., the engineering profession is not as well-known as it is in France, where it is tied more to the military than to other markets. In the U.S., engineering initially was tied to the automotive industry, similar to in Germany and Britain. And now in the more than 50 or 60 years since, the skills used in engineering are gaining a strong association with entertainment and other more lucrative fields, such as law.

She finds that many students feel they lack the math skills to go into this profession. She advised, “The number one, number two, number three thing I would say is to not doubt yourself, don’t think that you need to be an absolute perfect 100 average in math and science to be an engineer. What I find first and foremost is that women tend to think that unless they’re absolute rock stars in math and science, they cannot be an engineer. And I just really want to demystify this. It’s not true. Women suffer from a lack of self confidence in those fields, particularly when they’re young, primarily because of isolation, they don’t have enough peers to connect with.”

“If you have the interest and reasonable ability in those fields, go for it. But definitely do not think that every boy who graduates with an engineering degree is a rockstar because I can promise you that’s not the case.”

Georgia mentioned an alumnus who graduated from Georgia Tech and worked at Kimberly Clark. As an extremely successful black man, he often commented about being a terrible student at the university.

“He was completely open about it and he would regularly come on campus and talk about how he barely graduated because his GPA was so low. And part of it was he was having too much fun as a student, but part of it was also he just was not very committed. He liked math and science, but he was not very serious about his homework,” she said. “Women put so much pressure on themselves. ‘My GPA has to be perfect.’ No, no, no, and no. Obviously if you hate math and science with a passion in high school, then it’s not a good field. But if you like it reasonably well and you have good study skills, you can go really, really far.”

“Women should not think that engineering is just engines and cars. It’s an extremely broad field that you can work with. It can be a very people-oriented field. You really can help others, you can travel, you can make good money. It’s really a wonderful, wonderful field and I hope more women that have the interest and aptitude can go into it because there’s a lot of great opportunities in that area.”

“Engineering can be a stepping stone for so many other fields. The foundation of every engineering field is problem solving skills. So many employers look for people with problem solving skills, including law, medicine, and others.”

Filed Under: Engineering Diversity & Inclusion